Learn about Enlighten:

an epigenetic test taken during pregnancy that predicts future postpartum depression risk

Postpartum Depression

Postpartum Depression (PPD) is the most common complication of childbirth. While those with a mental illness are at increased risk, it occurs spontaneously in up to 15% of the population. That means it can happen to any mother to be. PPD is more than just being sad. Outcomes of PPD for the mother are severe and include suicide risk, which accounts for up to 20% of all postpartum deaths1. For infants, PPD impairs infant safety and healthy child development2,3, and leads to infantile colic and poor maternal-infant bond4. Because the early postnatal period is critical for neurodevelopment, the effects of PPD are further compounded, eventually affecting IQ, language development, and behavior5.

PPD often goes unrecognized. Affected mothers can confuse symptoms with the fatigue and stresses of caring for a newborn, which hampers treatment initiation. Once symptoms become severe enough to cause alarm, there may be long delays to reach services, impairing prognosis. Furthermore, protocols for communicating risks of PPD to prospective mothers are inconsistent, which could reduce awareness and delay treatment seeking 6,7. This lost opportunity to provide early intervention can have lifelong consequences for both the mother and the infant.

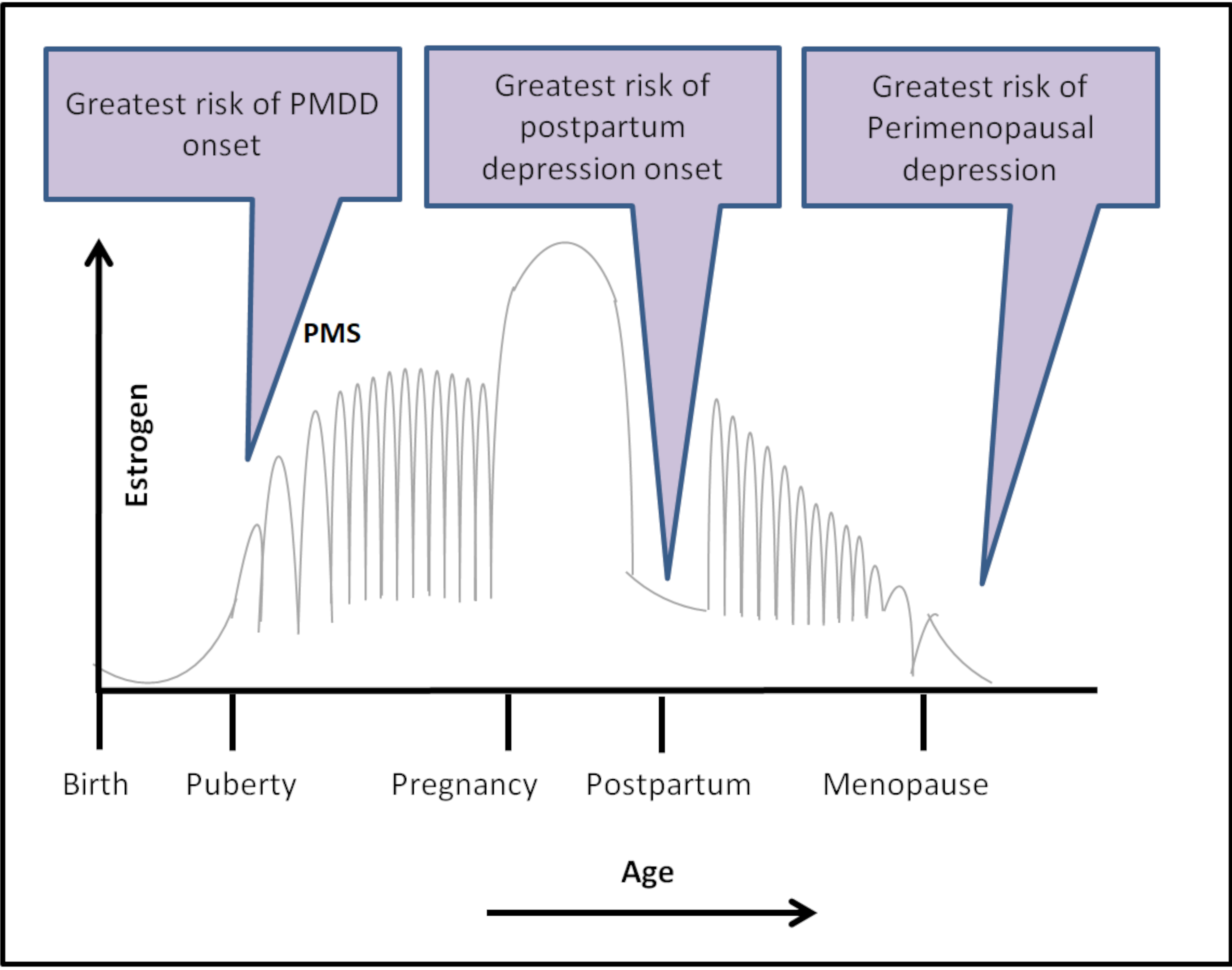

PPD is one of many types of depression that are related to periods of hormonal change. Others include premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) and perimenopausal depression (PMD). Like PPD, women with these depressions appear to be more sensitive to hormonal changes. This sensitivity can change a person’s epigenetics and gives us a way to measure susceptibility.

Epigenetics

‘Epi’ in epigenetics comes from ancient Greek, meaning ‘over or above’, IE: over or above the DNA. Epigenetic methylation of DNA act like light switches, turning genes on or off to express the right genes at the right times throughout life. For example, it is because of epigenetic patterns on top of the DNA that a cell in your liver is different from a cell in your brain, despite having identical DNA sequences. Anything that important for normal function has the potential to cause disease if it is on or off when it shouldn’t be. Importantly, unlike the DNA sequence itself, epigenetic patterns can be changed by our environments. Everything from diet and exercise to changing hormones to the stress we experience can change our epigenetic code. Because epigenetic patterns can be changed by these influences as well as someone’s underlying genetic make-up, measuring them can provide clues into a person’s underlying biology as well as environmental exposures and help us to predict disease. Hormones are an important epigenetic modifier involved in reproductive depressions and because hormones are circulating throughout the body, we can measure their epigenetic signature in blood.

Epigenetics and Postpartum Depression

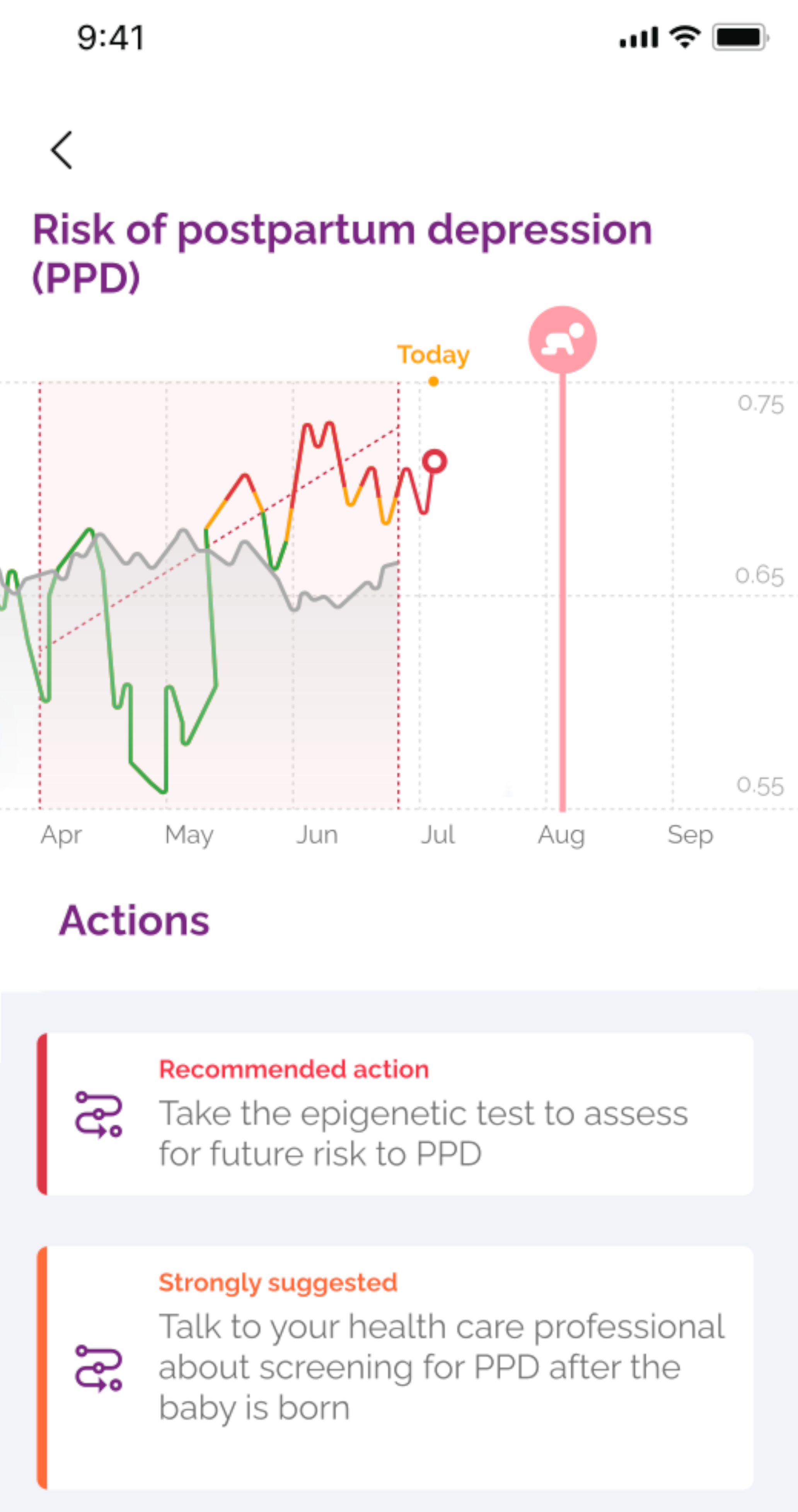

By scanning epigenetic biomarkers during pregnancy, we can predict a woman’s risk to developing depression after giving birth

Scientific evidence indicates that women at risk to reproductive depressions like PPD are biologically sensitive to periods of hormonal change8–12. Over a decade ago, we paired epigenomic profiling of estrogen responsive loci in the mouse brain with PPD associated methylome profiling of blood in human ‘mothers to be’ in order to find genes that would be sensitive to hormone withdrawal, identifying the first mental illness predictive epigenetic biomarkers. The methylation status of two of these genes, TTC9B and HP1BP3, when modeled together, predict future risk to PPD with >85% accuracy13. TTC9B is associated with estrogen activity 13, while HP1BP3 mediates anxiety in female mice and, when knocked out in pregnant mouse mothers to be, their pups die because the mothers stop taking care of them 14. Clearly these genes are important. Over the last decade, we successfully replicated the predictive ability of these genes in 6 additional published 15,16 and unpublished cohorts. Now it is time to bring this scientific success to you! What does your epigenetic future hold?

Protect Your Future

Other fields of health benefit from prognostic tests, allowing doctors and patients to act to reduce future disease risk. Why should mental health be any different? With PPD, knowing the future comes with benefits. A non-invasive private digital interface coupled with our ground breaking AI acts as a first step to help you understand your risk. Anyone can take the PPD blood test. Having a biological test showing you are at elevated risk to PPD will help you and your supporters to recognize symptoms if they develop. You’ll know you are more than ‘just tired’ and that it is time to get screened by your doctor so you can be treated. Having that extra support beforehand may even protect against PPD17,18.

Beyond PPD, we are developing other epigenetic tests to help you protect your future. These technologies will give you insight into other depressions caused by an epigenetic sensitivity to hormonal changes including premenstrual syndrome (PMS), premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), and perimenopausal depression (PMD). Other tests will let you know if you’ve been exposed to environmental risk factors or are at risk for cognitive decline. Beyond prognosticating risk, we are developing a technology to know if you’ll be likely to respond to antidepressants like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Did you know that many women (40~50%) don’t respond to these medications and right now the best doctors can do is to use trial and error over the course of many months to find this out? Nobody wants to flip a coin when they are in pain. Imagine getting the right medication from the start to alleviate your suffering sooner.

Mothers have a tremendous influence on their children. Maternal depressions like PPD can leave lasting epigenetic marks on the next generation that predisposes them to later life psychiatric risk. By protecting your own mental health, you’ll be protecting the future mental health of your family.

You are not alone. Dionysus is here to support.

Reveal your hidden biology Improve your mental health Protect your future

References

- Lindahl, V., Pearson, J. L. & Colpe, L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Archives of Women’s Mental Health (2005) doi:10.1007/s00737-005-0080-1.

- Flynn, H. A., Davis, M., Marcus, S. M., Cunningham, R. & Blow, F. C. Rates of maternal depression in pediatric emergency department and relationship to child service utilization. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry (2004) doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.03.009.

- McLearn, K. T., Minkovitz, C. S., Strobino, D. M., Marks, E. & Hou, W. The timing of maternal depressive symptoms and mothers’ parenting practices with young children: Implications for pediatric practice. Pediatrics (2006) doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1551.

- Akman, I. et al. Mothers’ postpartum psychological adjustment and infantile colic. Arch. Dis. Child. (2006) doi:10.1136/adc.2005.083790.

- Grace, S. L., Evindar, A. & Stewart, D. E. The effect of postpartum depression on child cognitive development and behavior: A review and critical analysis of the literature. Archives of Women’s Mental Health (2003) doi:10.1007/s00737-003-0024-6.

- Byatt, N. et al. Improving perinatal depression care: The Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project for Moms. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry (2016) doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.03.002.

- Byatt, N. et al. Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program for Moms: Utilization and Quality Assessment. Obstet. Gynecol. (2018) doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002688.

- Studd, J. W. A guide to the treatment of depression in women by estrogens. Climacteric (2011) doi:10.3109/13697137.2011.609285.

- Bloch, M. et al. Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. Am. J. Psychiatry (2000) doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.924.

- Bloch, M. et al. Cortisol response to ovine corticotropin-releasing hormone in a model of pregnancy and parturition in euthymic women with and without a history of postpartum depression. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. (2005) doi:10.1210/jc.2004-1388.

- Kimmel, M. et al. Oxytocin receptor DNA methylation in postpartum depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology (2016) doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.04.008.

- Osborne, L. et al. Replication of epigenetic postpartum depression biomarkers and variation with hormone levels. Neuropsychopharmacology (2016) doi:10.1038/npp.2015.333.

- Guintivano, J., Arad, M., Gould, T. D., Payne, J. L. & Kaminsky, Z. A. Antenatal prediction of postpartum depression with blood DNA methylation biomarkers. Mol. Psychiatry (2014) doi:10.1038/mp.2013.62.

- Garfinkel, B. P. et al. HP1BP3 expression determines maternal behavior and offspring survival. Genes, Brain Behav. (2016) doi:10.1111/gbb.12312.

- Kaminsky, Z. A. et al. Postpartum depression biomarkers predict exacerbation of OCD symptoms during pregnancy. Psychiatry Research (2020) doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113332.

- Payne, J. L. et al. DNA methylation biomarkers prospectively predict both antenatal and postpartum depression. Psychiatry Res. 285, (2020).

- Howell, E. A. et al. An intervention to reduce postpartum depressive symptoms: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Womens. Ment. Health (2014) doi:10.1007/s00737-013-0381-8.

- Howell, E. A. et al. Reducing postpartum depressive symptoms among black and latina mothers: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. (2012) doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318250ba48.

CONNECT AND THRIVE

Join the community

Do you have questions? Want to know more. Please contact us today.

© 2021 Dionysus Digital Health. All rights reserved.